Every now and then, a voice comes along that is so thoroughly in tune with the times that it can’t — and shouldn’t — be ignored. This year, that voice belongs to Rhiannon Giddens. Her latest album, Freedom Highway , takes its cues from the warriors of justice who came before her … Joan Baez, Odetta, the Staples Singers, and others. And it takes its stories from the victims of injustice that suffer throughout history … slaves, children, Black men, and more.

Of course, Giddens couldn’t have known that, in the middle of her album cycle, Nazis would march and Confederate statues would fall. But march and fall they have, all while she uses her voice to speak truth to the powers that be and the masses that care. And, in case anyone dare challenge her assertions, the ever-curious student of history brings all the proverbial receipts to back up her truth.

The more this year rolls along, the more important and potent your record and voice become. How’s it feel, at this moment in time, to hold up a mirror of the racial injustices upon which this country is founded?

Somebody said, at the show yesterday, “Your album is more timely every day!” I was like, “Yeah. Isn’t that depressing?”

Isn’t it?

Isn’t that freaking depressing? I wrote and recorded this record last year, and I remember thinking, before the election, “I don’t even know how urgent this is going to feel to people.” [Laughs] Little did I know. Holy moly! I mean, it’s always urgent to me, because I see it there. It’s always there, but for it to be so on the surface …

The thing is, the record’s always going to be timely because we’re talking about things that are part of the fabric of America — completely systemic issues here. It’s just, now, it’s really on the surface. Now it’s really exposed whereas, if the election had gone differently, these issues would still be here; they would just be covered up, underground a little bit more.

So, on the one hand, I’m like, “Oh, God. I can’t believe this is going on.” On the other, it’s, “Yeah.” But it’s great that people can see it. There’s a population of us that have known this stuff was there, and now everybody else can see it. I have to stay positive. We’re in the middle of what people are going to look back on, like in the ’60s. That’s what we’re in, right now. It’s a little freaky.

It is weird to be discussing the cause of the Civil War in 2017. And having to argue about what the cause was …

Oh my God. I know! The book I’m in right now is Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 16–whatever through the Stono Rebellion and, when you get into the beginning of the country — like the very beginning, the settlements in South Carolina and Virginia and New England — African-Americans are completely intertwined with how the country came into being. Culture-wise, music-wise, economics … for the numbers, the impact was enormous. And when you also look at the primary sources and how the European-Americans, soon to be called “white,” talk about African-Americans, it’s a pretty negative, horrible thing.

To have that be the basis of a country … to have the genocide of natives be the basis of a country … to have racial discrimination be how the country has operated for however long … I mean, sure, of course it’s still an issue, of course this is deep-seated stuff. We’ve had a lot of surface progress and we have had some deep progress. I witness the number of white folks that are like, “Whoa! What?! This is wrong!” And that’s progress to me because, when you look at the numbers for how long it took Abolitionists to get a stronghold, how long it took the religious movement to get a stronghold … when you look at the overall thing, that’s a really positive development to me. And that’s what gives me hope, that there has been a lot of change in people. It’s just the system and the people in power are operating from this old thing. Of course! Why wouldn’t they? They benefit from it!

And they were taught — and continue to teach — a false narrative about how the country was founded.

Yes. Exactly! That’s a problem. When people with an open mind learn the actual history, they are horrified. But, if that’s not what you’re taught … My empathy only goes so far, though, because there’s an Internet and there are lots of books. There are just people who don’t want to dig. I get it: There’s a lot of stuff to watch on TV or whatever.

But there are books out there. There’s all this amazing, scrupulously researched documentation that’s coming out. I just got a book a couple weeks ago. It’s called The Other Slavery and it’s all about the slavery of Native Americans. It just came out last year and it’s thick and it’s footnoted to within an inch of its life. It’s all primary-sourced material that he’s gathered and is writing about. You start reading and it’s like, “Oh my God!” But it’s out there in the book store. Pick it up.

I don’t know. I’m in between, sometimes. I understand if you think the narrative is this, but that only goes so far because you hit human decency. Even if your knowledge of American history is flawed, there’s still, “Don’t be a Nazi.” You know what I mean? I can go only so far with sympathy. It’s like, “Cool. Yeah. You have a swastika? I’m done.” It’s a weird place to be.

As an artist of color and a woman, do you feel any internal or external pressure to meet certain expectations with this stuff … because you don’t have the luxury of mediocrity, like so many white guys with guitars have?

[Laughs] Oh, boy! You don’t hear that very often! Right?

[Laughs] But it’s true. It’s not fair, but it’s true.

It is true. But it can swing the other way a little bit. I’ll be honest: Chocolate Drops, when we started, we weren’t very good. I mean, we were very enthusiastic. [Laughs] There was a novelty aspect that brought some people to the show, but what we had was a connection to tradition. And that is what got us over the beginning of not being that great.

But what you’re saying is … there are two different ways to look at it: There are systemic issues that affect everybody, and then there are issues that anybody has. Right? Everybody has a particular set of obstacles to overcome in their life and then there are these systemic things. So I try to approach my professional life by trying to look at it as this specific set of obstacles that I’ve been given as a human being and not looking at it from the systemic point of view because I think, especially when it comes to me, I have a lot of advantages: I’m light-skinned and all of that kind of stuff.

I remember having a conversation with Sharon Jones, when we were on the set of The Great Debaters. We were part of a music scene in the movie for a split-second. I had never met her before and listening to her talk about how hard her life had been primarily because of her skin color and going, “Wow. I had no idea how bad it could be.” I just shut up and listened to her talk because this was a woman a generation older than me and she had a lot of shit she needed to say, and I needed to hear it. Having that experience, I took that into myself and felt like, “I’m going to use my advantages and I’m going to not really think about what may not be happening for me because of who I am.” I have to stay focused on that because I do have advantages and I do have privileges. And I’m going to use that to try to tell these stories.

I’ve been very, very blessed. The Chocolate Drops were blessed. We stayed focused on Joe [Thompson] and the mission. I think that overcame lots of things. Yeah, we had our share of stupid remarks and what not. But, come on: I read the autobiographies of Black musicians who were out in the ’20s and ’30s and it was nothing, nothing, NOTHING, not even a fraction of what they went through. So I considered us blessed and I used that to try to tell these stories of people who are less fortunate.

You’re in a unique position to bridge a few different gaps, particularly doing the keynote at the IBMA Awards this year. How do you address a crowd that is, notably, not diverse? Some of them may well be allies, some may not. So how do you frame your message to a crowd like that for the biggest impact?

This is where growing up mixed comes in handy. You just walk the line and be unapologetic about it: “Look, man, this is where I’m coming from.” We’ve been shunned by white family members. We’ve been treated not great, so I know that experience. But you can’t hate people. Because I’ve also seen the progress that the white side of my family has made. My grandmother became a bastion of love. She treated us the same as all her other grandchildren. She led that charge so the immediate family could see, over the years, how that love warmed things. So I’ve seen how people can change.

That’s why I get frustrated when people on the Left talk about “those rednecks” and are really dismissive of people I’m related to. You have to give people an opportunity to change. My grandmother’s a great example: She was poor, white, Southern, always looking out for survival, just very simple, straight-ahead, North Carolina, out in the country … her husband built their house, that kind of thing. Her first-born son goes to the big city metropolis of Greensboro and finds a Black woman and becomes a hippie. She had two choices. She was not like, “Oh, that’s great! Bring the Black woman home!” because that wasn’t her experience. In her life, they were the “other.” When my sister was born, she was like, “That’s my grandchild.” She was worried and wasn’t sure what they were going to do, but, then my sister was born, and she was like, “I don’t really care. I’m going to love this child.” She was always really nice to my mom. There were others who weren’t, but she stood fast. That, to me, is so inspiring. That’s where true change happens — when people fall in love and they bring people in. I come from that place.

It takes the “other” out of the equation because the “other” is now part of your family and are no longer an “other.” Like you said, you have to get on board or step all the way off, I guess.

That’s it. That’s absolutely it. It’s interesting. I come prepared knowing the history, so there’s a calmness. I know what happened.

You have truth on your side.

Yeah. You can say whatever you want, but …

Is it tiring or rejuvenating to sing these songs night after night? Is your next project going to be light-hearted kids’ songs or are you going to keep tugging this thread?

[Laughs] Good question!

I hope you keep tugging the thread until the whole thing unravels, but if you need a break, you do your self-care, Gids.

I go back and forth. I’m figuring out ways of not depleting myself. I emailed Joan Baez and asked, “How do you do this? You’ve been doing this for 50 years!” She had some really smart things to say. You have to figure out a way to tap into it without going all the way. You can’t go all the way every night. You’re supposed to be a channel, not provide all of it. So I’m getting better at it.

Every time I think, “Oh, yeah, I’m going to do a love album next,” I keep reading and I’m like, “No way!” [Laughs] There are too many things to say, too many things to write about.

Tug, tug.

Yeah.

Is there anything you feel that’s gotten lost in the conversation around this record that you want to make sure to point out? Or are people really getting it in the right way?

I gotta say, people are getting it. They’re getting the record and they’re getting the show. I’m just kind of stunned, sometimes, when I read the responses and what people have to say. It’s really great. I feel really good about it. It’s been pretty amazing.

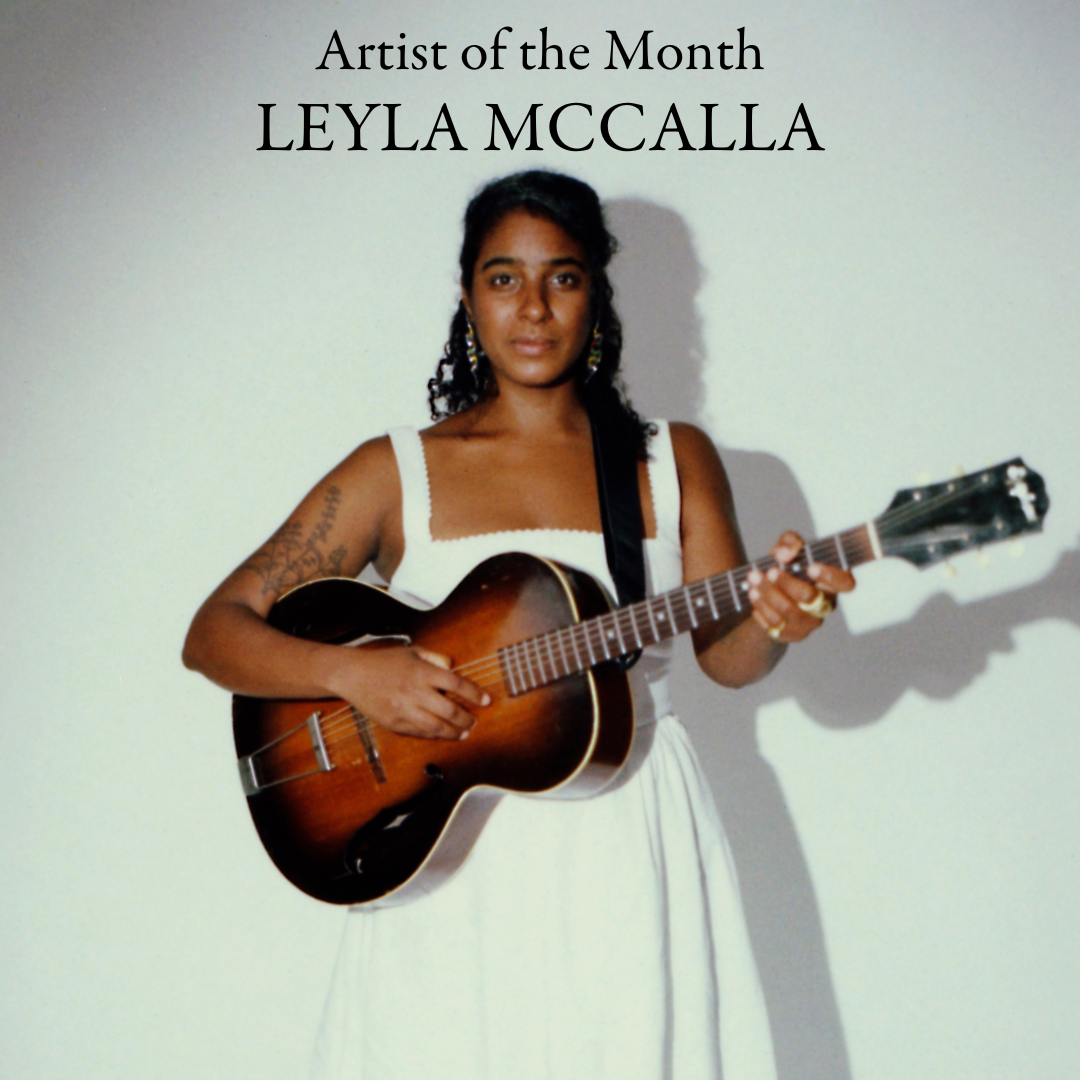

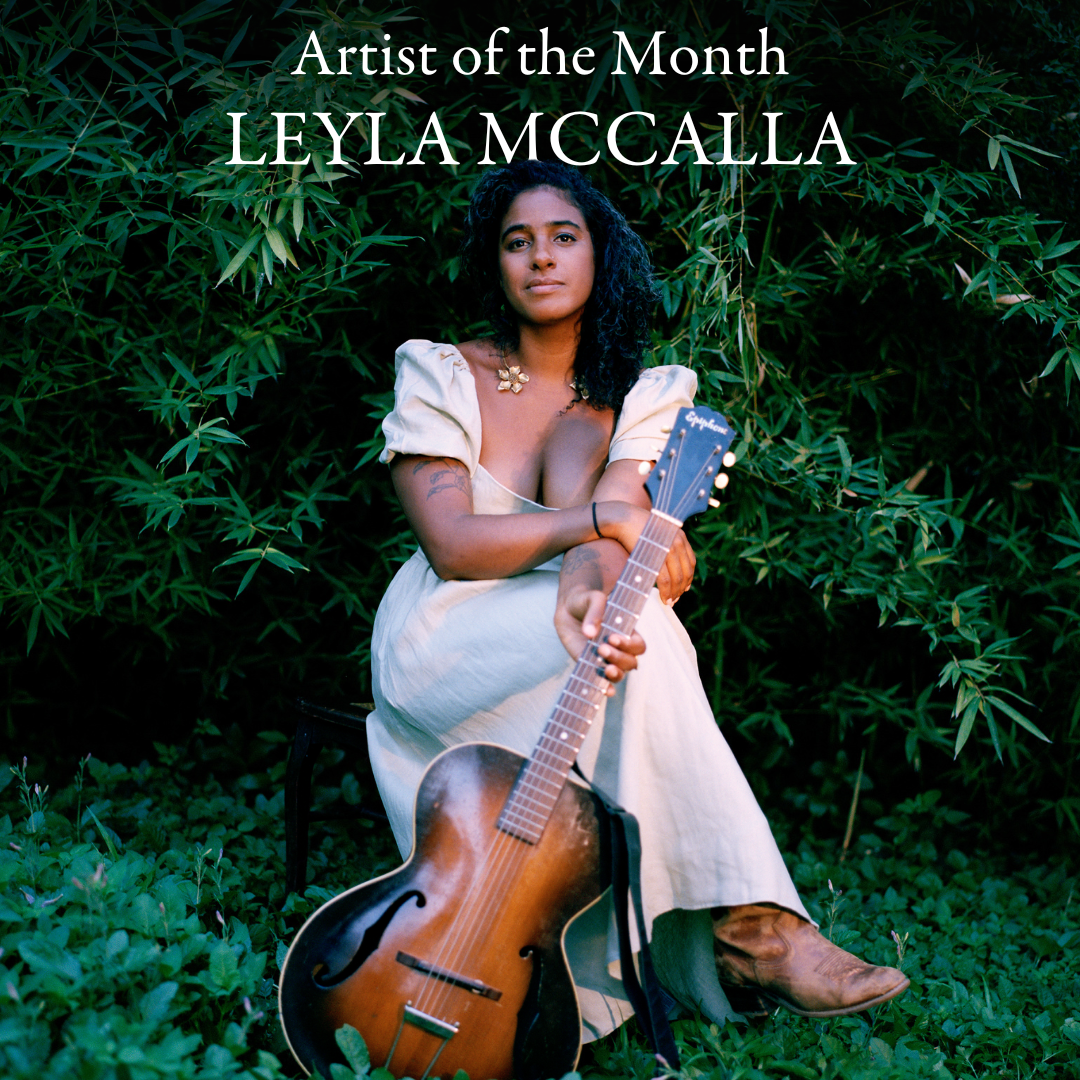

Photo credit: John Peets